The 20-year anniversary of the media sensationalising Frank Bruno’s decline in mental health served a timely reminder of why monitoring and reflecting on mental health and wellbeing is so important.

Frank Bruno was tough. A champion boxer. Charismatic. A big boy. And big boys don’t cry…right?

I also often think of someone who, perhaps for his wildly entertaining energy, filled my childhood with such joy…

As I got older, and understood his more adult humour, Robin Williams filled me with even more joy; he would have been the ultimate dinner guest. He spent his whole life making people laugh – he couldn’t have possibly felt low… right?

Two wonderfully different characters who, despite all the success in their careers, and deep love show towards them across the world, often found themselves in moments of terrible despair. Two men who spent time fighting the shadows in their minds – fights that perhaps people around them didn’t know were on.

Bruno is right in that his high-profile struggles contributed towards a major shift in the conversation around mental illness. However, many mental health responses, certainly in the school setting, remain reactive; intervention when something, sometimes catastrophic, has gone wrong.

Precarity and a lack of meaningful relationships

It’s fair to say that the fall in financial support for youth services, not to mention the strain of a digital world, where young people may feel pressured to present an all-singing and dancing version of themselves through social media, has contributed towards an increase in common mental health conditions among young people.

Anecdotally, some data suggest that a ground-zero moment in the decline of youth mental health and socialisation coincides with the launch of the very first iPhone, with early-age uptake of smartphones correlating strongly with the onset of several significant mental health issues (Sapien Labs, 2023). Strange, that.

Lower levels of face to face socialisation

The Child Mind institute suggests that screen-time is causing young people to grow up with lower levels of face to face socialisation, leading to higher levels of anxiety and an inability to recognise visual cues in other people. Device usage is essentially making people face inwards – on the self – without making meaningful connections with those around them.

Links between screen use and wellbeing

Twenge and Campbell (2018) found in a population study that non-users and low-users did not differ in mental wellness whereas high-users showed less curiosity, self-control and emotional stability.

These findings might support the notion of an exponentially increasing societal poverty, where a lack of relationships above the superficial is the new norm for those with faces buried in screens.

It’s certainly something I notice when working with many young people – not all – but many. However, the research doesn’t offer clear evidence to suggest that the use of social media specifically has a profound negative impact on mental wellness (Coyne et al., 2020) despite popular observations.

Screen time

My opinion – screen time is a problem. A recent exercise with a group of students keeping track of their screen time revealed that there wasn’t a student (of those who volunteered to reveal) who had less than 8 hours of screen time per day for the previous week. That’s 56 hours a week. That’s more than a full-time job.

One student had racked up 16 hours one Saturday. Another had achieved 3 and half hours on a Monday BEFORE school.

The thing that probably frustrates and amazes at the same time, is that these are the same students who you’ll hear saying ‘I didn’t have time to pack my PE kit” or “I haven’t had any time to complete my coursework”.

Precarity

There is also an ever-increasing number of students who are living in precarity (Kirk, 2020; 2021).

The term ‘precarity’ relates to living in a state of being uncertain or a situation that likely to get worse.

The Child Poverty Action Group found that, between 2021 and 2023, the cost-of-living crisis has pulled a further 350,000 children in the UK into relative poverty, with 29% of all children in the UK now in poverty.

In the immediate future of the UK, a country still reeling from the economic damage of events such as COVID and Brexit, we can probably presume this is going to get worse.

In summary

So – an increasing number of young people are living in precarity, which may be compounded by the lack of meaningful relationships to rely on in moments of difficulty. A grim combination, and a sad reality for many of the students we interact with daily.

But as Bruno and Williams’ respective stories tell us; poor mental health isn’t reserved for just those without financial security or meaningful relationships – everyone’s mental health fluctuates for a myriad of personal reasons, and we need to look out for each other.

Promoting mental wellness

In Ben Holden’s recent blog, whilst discussing how he tackles PE-refusers, he observes that “being fully informed on a pupil and the intricacies of their personal situation” is absolutely key to breaking down barriers and addressing the needs of our students.

This is a proactive approach to school processes around mental health and wellbeing – with the National Children’s Bureau’s (NCB) (2016) whole-school framework signalling this as essential.

NCB framework guidance

The NCB framework guidance states that, when dealing with student mental health in the school setting:

· Most student mental health issues are not clinical in nature;

· Staff need to understand and can identify signs and triggers of concerns; recognising the need for early intervention;

· Relationships are KEY

· Wellbeing evidence is drawn from students themselves.

· School systems should become proactive and pre-emptive in student mental health

Self tracking technologies

For a more proactive and pre-emptive approach, I sought to use self tracking technologies that could give my school a better understanding of student perspectives, the lives they lead, the worries they have, and the difficulties they faced.

Personal informatics systems

Personal informatics systems is a growing area of technology that focuses on self monitoring and reflection. These systems traditionally engage technologies in the health sector to encourage patient generated data (Wang, Ding and Hirskyj-Douglas, 2023). Self-tracking applications have been effective in promoting physical activity, weight loss, medication adherence and stress management through goal-setting and monitoring progress over time.

Research also suggests that self-tracking through personal informatics systems can play a significant role in promoting well being and self efficacy. A recent study with college students examined the use of wearable devices to monitor mental health and wellbeing.

Leveraging self tracking of wellbeing using a continuum

I wanted a system that would provide staff with the information needed to build strong relationships with students which radiated compassion and empathy. What started as a physical activity tracker for students during COVID lockdowns soon developed into something far more significant.

To ensure students would be more inclined to engage with this system, I decided that the input of a reflection needed to be a rapid task that would not demotivate or deter engagement. So many student mental health surveys ask too many questions – I wanted self tracked data that would take a few seconds to gather.

Additionally, I felt students needed the ability to record a reflection at their convenience, albeit at home or in school.

Collecting everyday mood through simple language

Young people experience a tension between the need to disclose and the stigma associated with a disclosure (Park et al., 2020); they don’t necessarily want attention from school staff or peers. The importance of self-image in front of peers is heightened during adolescence, and students will seek to avoid embarrassment (Blakemore, 2005).

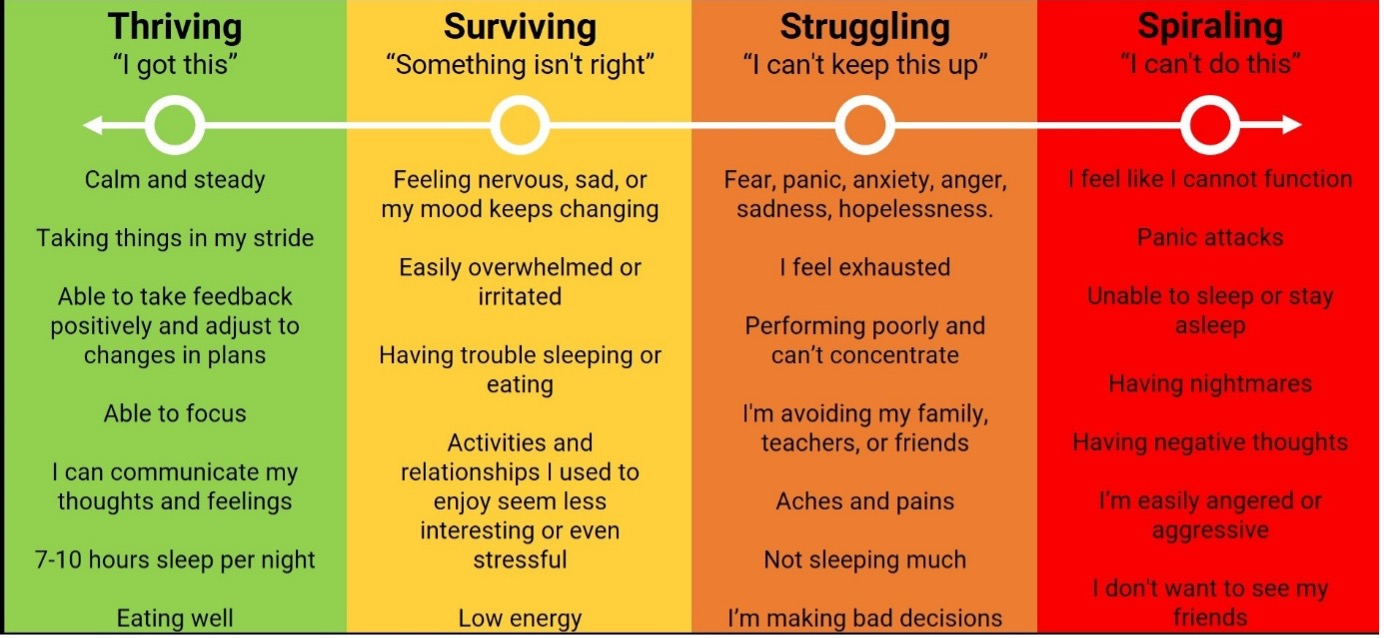

To remedy this, when collecting everyday mood, we took the need for “big conversations” away from students who would likely lack the confidence or emotional literacy to have them, and instead offered students a continuum of school friendly language to reflect against.

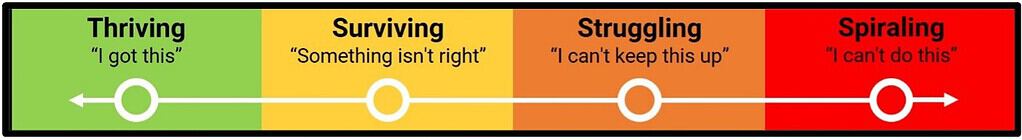

Figure 1 – The wellbeing continuum used within the tracker.

Promoting mental wellness through an activity log

Adapted from a stress first-aid manual produced for firefighters and emergency service personnel, Figure 1 was designed with ease of use in mind.

The “ings” of “Thriving, Surviving, Struggling, Spiraling” chosen specifically as they represented temporary states where students could understand movement between them.

As Rainer Maria Riike would say – “just keep going, no feeling is final”.

Sharing self tracked data to support mental wellness goals

Recording a reflection became a simple task of selecting the appropriate word via a QR code and adding a comment if they desired. It took most students between 5-20 seconds. There was an additional question asking if they’d like to make a record of a wellbeing activity that they had taken part in, and sharing self tracked data entries resulted in positive points on our school’s behaviour system.

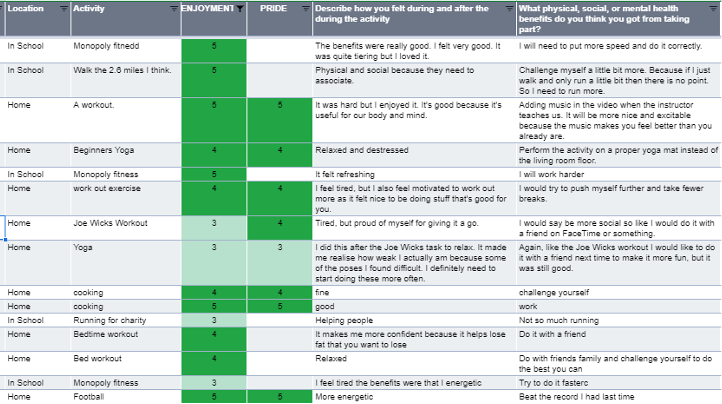

The wellbeing activity log (Figure 2) was designed with the purpose of engaging students in positive affirmation of the impact different self care activities had on their wellbeing to support mental wellness goals. The positive points would then encourage them to record and evidence further logs.

Engaging students in self reflection and discussion of positive experiences is just as valuable as discussing when it is not, which is a fundamental part of the Health and Wellbeing AOLE in the Curriculum for Wales (more on that later) and understanding how experiences affect student mental health and wellbeing.

Figure 2 – The wellbeing activity log asked students to measure their enjoyment and pride experienced by taking part.

Whole School-Overview

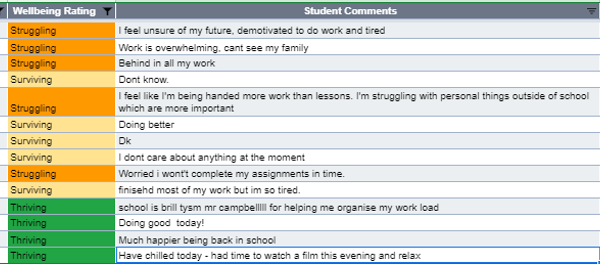

A whole-school dashboard provided live self tracking data that was accessible to the pastoral team and teaching staff, whilst also providing an overview of the responses within different year groups.

With student self reflection coming in live, our school had a pastoral-support monitor incoming responses, and we aimed for students self-reporting as “Spiraling” to be picked up, in person, within 15 minutes of reporting it.

Identifying trends

Identifying trends in the self tracking data was key to the tracker having a positive impact on the lives of students.

For example, one student (Figure 3) made repeated references to workload becoming a significant stressor for them and their family commitments. Although many small interventions took place with the student, it was evident by their self reflection towards the end of the period that an hour spent after school with me to organise a weekly homework timetable, and to help prioritise assignments by hand in date, helped this student to move towards the positive end of the wellbeing continuum.

Proactive approach

Engaging with the student’s personal issues around workload was a proactive approach to stress management because although they felt they were falling behind, they were not at all, and action was taken to avoid their fears becoming realised. Doing everything right and well didn’t mean anything to this student, because they could not see it, and as a result they were suffering.

These reflections further informed my actions in the following term, where I spent more time organising assignment requirements for this student to ensure they were not overwhelmed.

The “Struggling” responses soon became a thing of the past.

Figure 3 – The chronology of responses for a student who struggled with coursework and how an intervention had a positive impact on self-reported wellbeing.

Responding to trends

In thematic analysis of the comments added by students, several wider health and wellbeing themes were addressed in lessons. In my setting for example, students were regularly tracking sleep and reporting that they were not getting enough. Through this data analysis, we delivered a sleep hygiene unit to Key Stage 3. This is a good example of student self reflection data being used to inform curriculum decisions.

Tracking student self perception of wellbeing

The self reflection tracker formed part of a whole-school strategy to student mental health and our work towards the Curriculum for Wales and its Health and Wellbeing Area of Learning Experience (AOLE).

The second “What Matters Statement” of the AOLE seeks to help students understand how we process and respond to our experiences affects our mental health and well-being.

Aims of the tracking tool

My aim when designing and implementing this tracking tool was to encourage self awareness in students and ensure they were able to:

1. Explore the connections between their experiences, mental health and well-being;

2. Develop strategies which help regulate emotions and contribute towards good mental health and well-being – such as seeking help (through the tracker) and encouraging stress management and self care;

3. Create a culture where talking about mental health and emotional well-being is normalised by the communication of feelings (through digital and private means in this case) to develop positive relationships and improve outomes.

With over 5500 reflections recorded by students in just over 2 years, the tracker has become a valued tool in understanding the lives of our students and working together to improve wellbeing. Working together to create a culture where wellbeing is taken seriously.

Reflections:

1. How do you find out about the wellbeing of your students in your setting?

2. Do you collect data about the wellbeing of your students, and if so, how is it being used meaningfully to inform your practice?

If you have any questions about the tracker or implementing a fully automated system like the one I’ve created, please feel free to contact me at Jon@PEScholar.com.

The tracker described briefly in this article was created for free on Google Suite and has other data fields and analysis tools.

References

Coyne, SM., Rogers, A., Zurcher, JD., Stockdale, L., Booth, M. (2020) Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study, Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 104, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5103&context=facpub

Feustel, C., Aggarwal, S., Lee, B. and Wilcox, L. (2018) People like me: Designing for reflection on aggregate cohort data in personal informatics systems. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(3), pp.1-21.

Kirk, D. (2020) Precarity, Critical Pedagogy and Physical Education, London: Routledge.

Kirk, D. (2021) Precarity, the health and wellbeing of children and young people, and pedagogies of affect in physical education-as-health promotion [Online] Available at: https://pure.strath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/131075429/Kirk_ED_2021_Precarity_the_health_and_wellbeing_of_children_and_young_people_and_pedagogies_.pdf [Accessed 25 Oct 2022)

Sapien Labs (2023) Age of first smartphone and mental wellbeing outcomes. Available ONLINE: https://sapienlabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Sapien-Labs-Age-of-First-Smartphone-and-Mental-Wellbeing-Outcomes.pdf

Twenge, J.M & Campbell, W.K (2018) “Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study”, Preventive Medicine Reports, Volume 12,2018, Pages 271-283, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211335518301827)

Wang, W., Ding, X. and Hirskyj-Douglas, I. (2023) July. Everyday Space as an Interface for Health Data Engagement: Designing Tangible Displays of Stress Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (pp. 1648-1659).

Responses