What Is Freestyle Gymnastics?

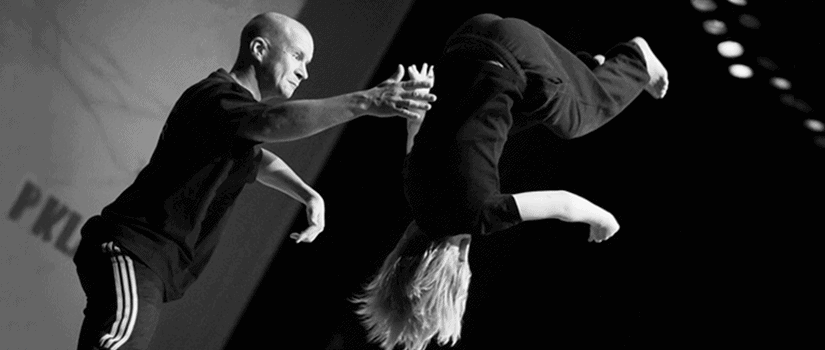

In the summer of 2013, British Gymnastics officially launched FreeG, a new brand created to promote the exciting and fast growing activity of freestyle gymnastics, and support clubs and leisure centres wanting to offer the sport. Freestyle gymnastics is a modern form of gymnastics, which combines traditional gymnastics, dynamic acrobatic tricks, stunt performance, and kicks and jumps better known for their use in martial arts. Alternative sports like freestyle gymnastics have seen a rapid growth in popularity in recent years, in part due to the creativity and self-expression they offer. Participants are encouraged to pick the stunts and movements they want to incorporate into their routine, drawing from a diverse range of other sports. This more interpretive approach appeals to individuals wanting to explore gymnastics in a less formal way, whilst still providing a range of physical and psychosocial benefits.

Physical Benefits

Freestyle gymnastics brings with it all the advantages of traditional gymnastics, along with those of martial arts disciplines. It helps meet the daily national health exercise recommendations: for 5 to 18 year olds this is at least an hour each day of physical activity of between moderate and vigorous intensity, which should include muscles strengthening activities on three days each week (NHS, 2013). Gymnastics falls into the moderately intense category, and is widely renowned as a sport that can improve overall fitness, strength, balance and coordination. Participation in activities such as freestyle gymnastics can help maintain a healthy body, which is key to preventing numerous ailments, and research has shown that these benefits remain long after gymnasts have retired from the sport (Eser, Hill, Ducher & Bass, 2009). Children can benefit especially from freestyle gymnastics, as regular exercise at a young age has been proven to lower the ricks of obesity and related illness later in life (Reilly & Kelly, 2011).

Gymnasts are well known for their excellent strength-to-weight ratio, as taking part in gymnastics at a young age contributes to great all round muscles strength, power and endurance. A study by Burt et al (2011) investigated the association between non-elite gymnastics participation and bone strength, muscle size and function in young girls and found an increase of musculoskeletal benefits in those individuals who practised gymnastics, including greater forearm bone strength, greater lean mass, muscle power, endurance, and a lower risk of fracture. Motor skills, coordination and balance have are also improved through the regular practice of gymnastics, as well as the development of body awareness. A young gymnast learns to use various parts of the body in different ways, in coordination, which can have secondary benefits in other sports, physical activities and everyday tasks.

Academic and Psychosocial Benefits

There are additional advantages from both gymnastics and martial arts to educational and cognitive performance. One such area is spatial awareness; a concise understanding of the body in space and the relationship to other objects in that space. The development of a heightened sense of spatial awareness has been linked to the improvement of mathematical understanding, especially in areas involving abstract processes such as geometry. One study by Cheng and Mix (2014) looked at the effect of spatial training on math performance in 6 to 8 year olds, and found that it had a positive effect on performance of calculation problems. Brain imaging studies and behavioural evidence both suggest a compelling connection between space and math that point to spatial training as a means of improving performance in the STEM subjects (Lubinski, 2010; Uttal et al, 2012). Freestyle gymnastics could therefore support the development of spatial awareness in children, and support advancement of other subjects such as science, technology, engineering and maths.

For young girls particularly, greater body awareness through exercise can have a positive impact on self-esteem (Ekeland, Heian & Hagen, 2004; Furnham, Badmin & Sneade, 2010). There are varying theories regarding the cause; an increased number or awareness of compliments regarding improved body condition due to physical activity, a sense of achievement from approaching their own or others’ ideal body image or behaviour, or self-confidence due to setting and meeting physical goals. Petty, Davis, Tkacz, Young-Hyman and Waller (2009) studied the effect of exercise on depressive symptoms and self-worth in overweight children and found that engaging in regular, vigorous aerobic exercise with peers in an organised environment had a clear impact on depressive symptoms. Girls may also view freestyle gymnastics as a more appealing activity due to its less competitive nature. With this in mind, various school-specific courses and local groups have begun to pop up across the UK, in the hope of encouraging more young people to take part.

References

- Burt, L.A., Naughton, G.A., Greene, D.A., Courteix, D., Ducher, G. (2011) Non-elite gymnastics participation is associated with greater bone strength, muscle size, and function in pre- and early pubertal girls. Osteoporosis International, 23(4)1277:1286. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21660556/ [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- Cheung, Y., Mix, K.S. (2014) Spatial Training Improves Children’s Mathematics Ability. Journal of Cognition and Development, 15(1)2:11. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15248372.2012.725186#abstract [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- Eser, P., Hill, B., Ducher, G., Bass, S. (2009), Skeletal Benefits After Long-Term Retirement in Former Elite Female Gymnasts. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 24(12)1981:1988. Available at: https://asbmr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1359/jbmr.090521 [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- Ekeland, E., Heian, F., Hagen, K.B. (2004) Can exercise improve self-esteem in children and young people? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(11)792:798. Available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1725055/ [Accessed February 27th 2015]. - Furnham, A., Badmin, N., Sneade, I. (2010) Body Image Dissatisfaction: Gender Differences in Eating Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Reasons for Exercise. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 136(6)581:596. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00223980209604820#.VPROE7OsV8s [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- Lubinski, D. (201) Spatial ability and STEM: A sleeping giant for talent identification and development. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(4)344:351. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019188691000156X [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- NHS (2013) ‘Physical activity guidelines for children and young people’. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/Live-well/exercise/exercise-guidelines/physical-activity-guidelines-children-and-young-people/ [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- Reilly, J.J., Kelly, J. (2011) Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. International Journal of Obesity, 35(7)891:898. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20975725/ [Accessed February 27th 2015].

- Uttal, D.H., Meadow, N.G., Tipton, E. Hand, L.L., Alden, A.R., Warren, C., Newcombe, N.S. (2012) The malleability of spatial skills: A meta-analysis of training studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(2)352:402. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/search/display?id=a363ba43-0477-f452-2eb9-7919b906bd4f[Accessed February 27th 2015].

Photo: Werner Olsen

Responses