New Book Club

We have been talking about starting a ‘book club’ to review and share some of the great reading in and around PE, sport and physical activity for some time and what better way to kick it off. I knew that bringing the brilliant minds of Dr Ash Casey and Prof David Kirk together would produce something insightful, challenging and aimed at closing that research-practice gap for the benefit of todays young people and this book did not disappoint.

Models Based Practice

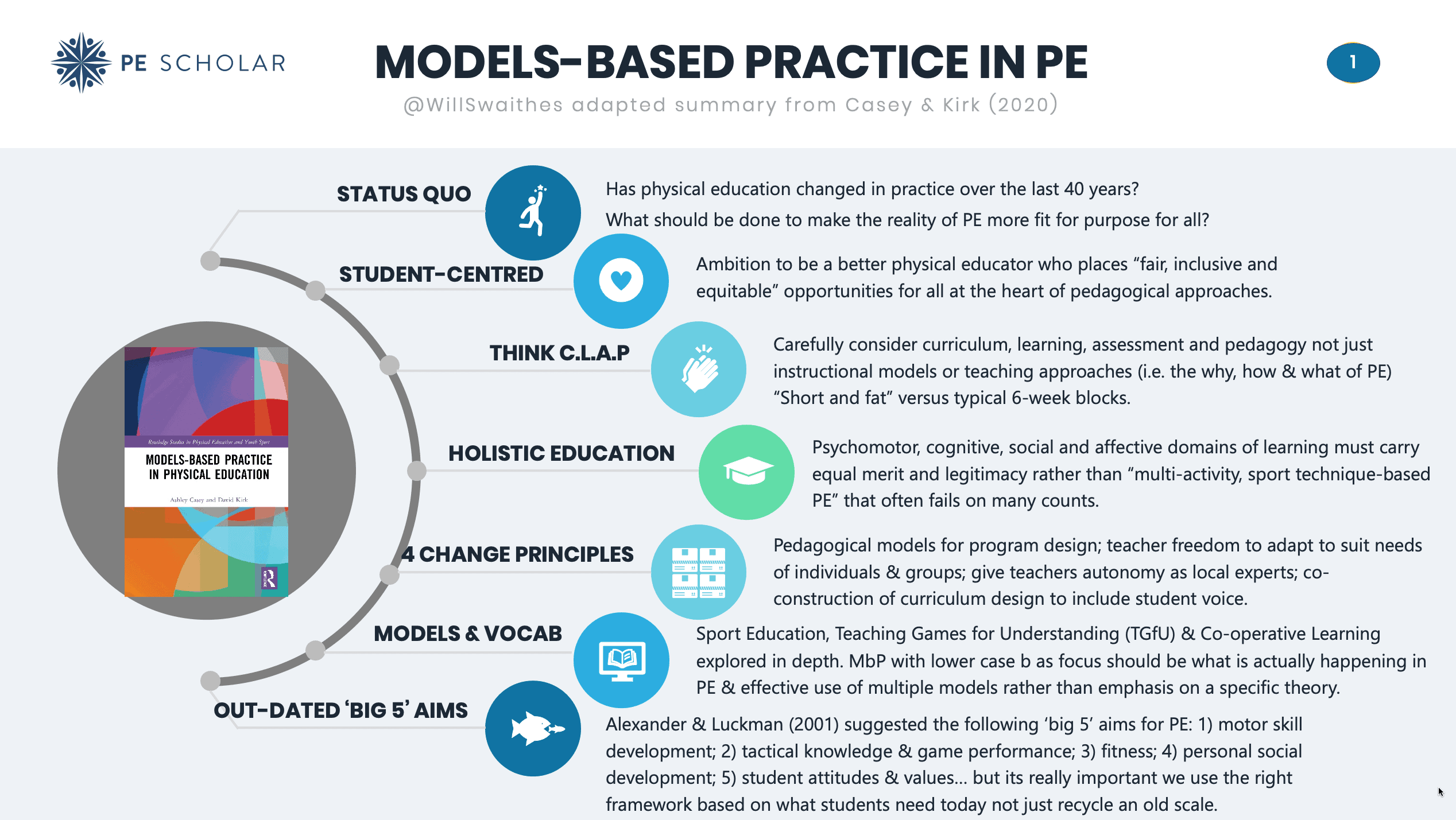

Models Based Practice challenges the status quo in physical education delivery. Combining a comprehensive review of key contributors to models-based practice (MbP) research over the past 40 years before suggesting what should be done to make the reality of PE more fit for purpose for all young people. It majors on Sport Education, Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) and Co-operative Learning but also touches on other pedagogical models as Ash and David explore the different levels and lenses of consideration.

Central to the ambition of the book (and their life work) is the hope that, collectively, we will do better for future generations of young people as they journey in and through physical education. Always framed through an ambition to be a better physical educator who places “fair, inclusive and equitable” opportunities for all at the heart and centre of pedagogical approaches. In other words, this is about much more than curriculum design or instructional models as it combines teaching, learning, assessment and the curriculum to take a holistic and student-centred look at the why, how and what of PE.

Psychomotor, cognitive, social and affective domains of learning carry equal merit and legitimacy but the dominant “multi-activity, sport technique-based physical education” offer fails on many counts. It fails to be inclusive of all young people and it fails to provide educative benefits worthy of the time and cost commitments. This is not through a lack of desire, demand or resource but it certainly appears to be falling short of its potential. Kirk suggests that in Scotland alone PE teacher salaries are costing around £80 million a year. Add facilities, equipment and teacher education on top of that and the authors suggest taxpayers “would reasonably expect to see [greater] tangible benefits to children and young people for recurrent spending on this scale” (p3). I am sure you agree and that you also agree this is not an easy one to solve. With “classes of 30 or more students, with wide ranging motivation for and competence in specific activities, even the most capable teacher is likely to be challenged to provide worthwhile educational experiences for all” (p7). However, as 2020 has proven, physical educators are not short of ambition, innovation or operational skill when it comes to needing to respond to a changing environment so why are we so resistant to pedagogical change?

Casey and Kirk identify four principles that underpin change (p9-12), and they are as follows:

- A new organising centre for program design: the “pedagogical model” – it is imperative to consider curriculum, teaching, learning and assessment in a combined manner if we are to shift thinking

- The “curriculum-as-specification”: sustainable adaptation – it is essential that individual teachers are given the freedom to adjust and continually adapt to suit the needs of individuals and cohorts rather than a prescribed list of content

- The eternal tension: balancing local agency and external support – teachers are the local experts and as such they need the autonomy to make the right choices but also to be challenged and supported in equal measures by curricula expectations

- Co-construction of physical education teachers, students, stakeholders – the young people themselves should also be involved in the design process.

Chapter 2 explores different models and vocabulary used in this space and, if I am correct, Casey and Kirk have adopted that lower case b in MbP to represent what is actually happening within physical education rather than a specific theory. It is suggested that true MbP does not yet exist but the idea of structuring PE around models rather than content (e.g. invasion games) and critically around use of more than one model (e.g. Sport Education, TGfU, and Co-operative Learning) is something that more physical educators could and should be doing.

In chapter 3 the main idea, critical elements, learning aspirations and pedagogy of Sport Ed, TGfU, Co-operative Learning, Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) and activist approaches are unpicked in detail.

Chapter 4 draws on what Alexander and Luckman (2001) call the “traditional ‘big 5’ aims of PE.” These are:

- Motor skill development

- Tactical knowledge and game performance

- Fitness

- Personal social development

- Student attitudes and values

Later work by Harvey and Jarrett (2014) unpicks how Sport Education and game-centred approaches like TGfU increase the likelihood of delivering against these big 5 aims in contrast to dominant “multi-activity, sport technique based physical education”. Explicit and implicit teachings are explored. As Ash shared with me recently, it is important to consider the right framework for what is needed by your students today not use an old scale in a new space and situation.

Understanding what these could look like in practice via further investigation of several specific papers is the focus on chapter 5. It is highlighted that drift between ‘model-maker’ aspirations in terms of a blueprint for delivery and teacher interpretation/ adaptation to suit specific needs is not only to be expected but also to be encouraged.

Considering the implications for timetabling, curriculum planning, teacher education and assessment of pupil learning becomes the focus in chapter 6 when Casey and Kirk ponder reorganising physical education. Finally, chapter 7 identifies the conditions needed for MbP to become a reality in PE. For example “short and fat” units of work may be needed to provide more intense learning experiences required for TPSR rather than the norm of 6 lesson blocks. Perhaps the combined forces and action research of trainee teachers, their in-school mentors and teacher educators holds the key to further exploration and realisation in this space?

This valuable read has cemented my belief that PE has somewhat lost its way and is led by what is easy, traditionally expected and I dare say worked for many who pursue a career in physical education when they were at school but that is not to say it is right or in the best interests of the many more ‘not like me’. As Casey and Kirk conclude, “physical education has much more to offer young people than this [multi-activity, sport technique-based program] dominant approach can deliver.” I’m up for the challenge, are you?

The next book in this series digs deeper into how to do MbP – I really look forward to that one too.

Here is a list of other book reviews you might want to check out:

Reviews by topic

Health and wellbeing

Happiness Factories: A success-driven approach to holistic Physical Education (podcast)

Time to RISE Up: Supporting Students’ Mental Health in Schools

Physical Education Pedagogies for Health

Inclusion and social justice

Inclusive PE for SEND Children and podcast

Teaching Disabled Children in Physical Education

Pedagogies of Social Justice in Physical Education and Youth Sport

Pedagogy

Perspectives on Game-Based Coaching

The Future of Teaching and the Myths That Hold it Back

Meaningful PE – an approach for teaching and learning

Threshold Concepts in Physical Education

The Spectrum of Teaching Styles in Physical Education and podcast

Reading lists

Also, don’t forget to take a look at these books published by Scholarly – indispensable additions to every PE teacher’s bookshelf.

[…] Models based Practice by Ash Casey and David Kirk […]

[…] (CL) is one of a small number of models that are used fairly extensively and successfully in PE. Casey and Kirk unpick many of the key features in their 2020 book but for a deeper dive into CL I highly recommend […]

[…] Models-based Practice […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]

[…] Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education […]