Introduction

I have thoroughly enjoyed this book by Rob Gray; so much of the research and thinking aligns with my philosophy and pedagogical approaches when it comes to teaching and coaching. As a physical educator who has challenged the skill-drill style of delivery and PE as sport-technique instruction for some time, I have obviously latched onto the work of David Kirk, Ash Casey, Michael Quennerstedt, Shane Pill, Margaret Whitehead, Michael Metzler, Tim Fletcher and a whole host of others but ‘how we learn to move: a revolution in the way we coach and practice sports skills’ has given further food for thought and reinforcement that a more creative style of lesson delivery is the way!

How we learn to move is skilfully broken down into 15 easy to consume chapters with just the right amount of academic referencing, anecdotes and real-life examples for me. Gray had me nodding along right from the preface where he described a scene I recognise all too well – youth sport dominated by static and isolated drills structured around elaborate cone setups and dreary routines. The idea of PE teachers and coaches acting as ‘innovative practice designers and guides’ as opposed to instructors is certainly a role that worked better for me over 14 years of exploring teaching styles and often yields better results from the trainee teachers I am fortunate to observe on a weekly basis. Starting out from a position of exploration and discovery rather than accurate replication of the ‘perfect’ technique may take longer to see progress (actually momentary performance), but it is often a lot more exciting and meaningful to young people and is certainly a lot stickier in terms of learning gains. As my wife is a physio, the evidence around reduced likelihood of injury by moving beyond the idea of one “correct” technique that is repeated to mastery also resonated with me. I have also added the ‘Perception and Action Podcast’ to my regular listen list as a result of this read. Having seen and heard so much about the sheer number of young people who are dropping out of sport and physical activity at an early age, I am in no doubt that (as Gray describes it) a revolution is needed. I am also happy to say that the revolution has started, across physical education and youth coaching there are pockets of great practice but for all young people to flourish and, seemingly, if we want to produce more sporting champions (although this is not the role of PE), this needs to become more common practice.

We will soon dive into a few of the 15 chapters that hooked me the most. I hope this gives you a flavour of what to expect and encourage you to also flick to the back of the book where you will find a number of ‘exploration guides’ with helpful infographics and suggestions on what to listen to, read, and watch if you want to dig deeper on a specific topic (e.g., constraints-led approaches, differential learning or an ecological approach to sports injury). Before we dive in, you might like to watch this quick video by the man himself:

Chapter 1: The myth of the one “correct”, repeatable technique

Chapter one provides great evidence to challenge traditional approaches of skill acquisition via rote and repetitive learning. We learn that questioning the idea of supporting performers to master that one correct technique is not even a new thing. In 1922 Nikolai Bernstein, a Soviet scientist, used cyclography to demonstrate that expert blacksmiths utilise vastly different movements at the shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand to execute precise and repeatable strikes of a hammer on the chisel and from this Bernstein coined the phrase “repetition without repetition” (p5). This demonstrated over 100 years ago that experts adjust ‘on the fly’, their joints work together to correct each other and ensure the right end result is achieved without the need for an exact and highly repeated flight path. Gray sums up this chapter nicely by saying ‘skilful movers do not achieve their goal by moving the same way every time – there is significant intra-movement variability within performers’ (p12). Combined with the fact that experienced individuals vary their movement significantly even when performing the same outcome, there is even more variability between experienced performers and hence surely the idea of repetition practice to imitate the perfect technique is seldom effective?

Chapter 2: We are built to produce and detect variation

Chapter two zooms out to describe how higher heart rate variability (HRV) is a good thing. ‘Image jitter’ helps us perceive moving objects and our eyes continuously make tiny movements to prevent ‘perceptual fading’ (objects that are not moving from disappearing from our consciousness) and enable better gathering of information from an image or our environment (p14). These are just two examples of Nike describes us as ‘designed to move’. This chapter goes on to explore the importance of increased ‘noise’ to help heighten senses rather than the traditional view of needing to block it all out. The words of tennis great Rafa Nadal describe “every shot is different; every single one” (p20) thanks to ever changing internal and external conditions (from fatigue and microtears inside different muscles to weather conditions, different opponents tendencies and the environment on the outside). We are designed to move and to be able to adapt to the ‘complex, ever-changing environment’ around us (p25). Consequently, do you still think the best way to learn new skills is via repetition practice?

Chapter 3: The business of producing movements and why we don’t need a boss

Chapter three explores Bernstein’s ‘degrees of freedom’ (the number of different ways a movement can performed) and describes the evolution of understanding around how we learn to move through three progressive analogies:

- The “cortical keyboard” – the musician in our brain sends a message down the spinal cord to command muscles to create a specified movement rather like pressing the keys on a piano

- The super-computer – building extensive stores of knowledge in the long-term memory to be accessed via the information processing model and limited by working memory

- Running a business called “Let’s Move Incorporated” – instead of the traditional linear model of the boss or CEO passing messages down through the middle managers (motor cortex) to the workers (muscles, tendons, joints etc) perhaps a ‘self-organising’ system that is able to adapt and respond to an ever-changing environment is a better fit (p42)?

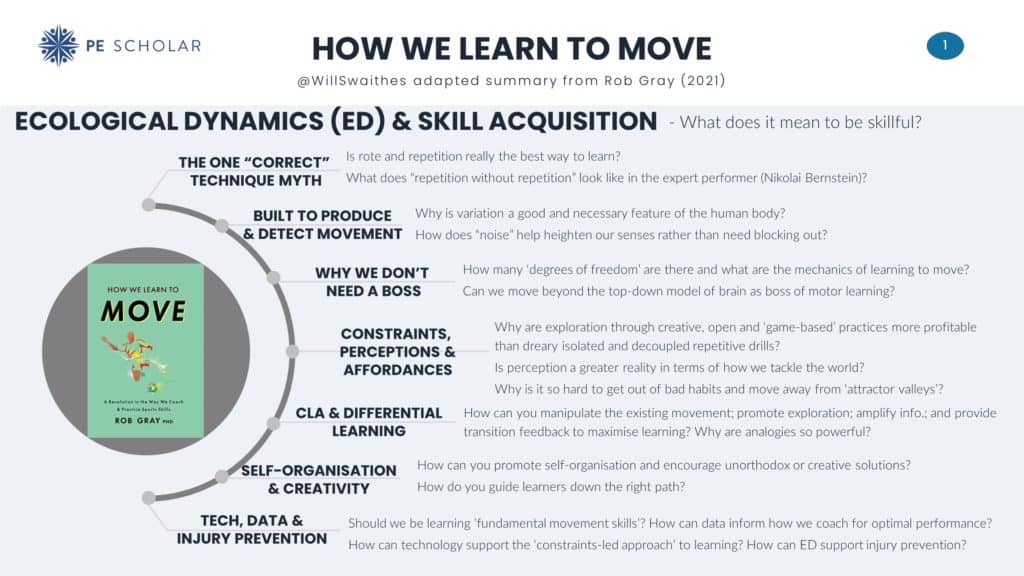

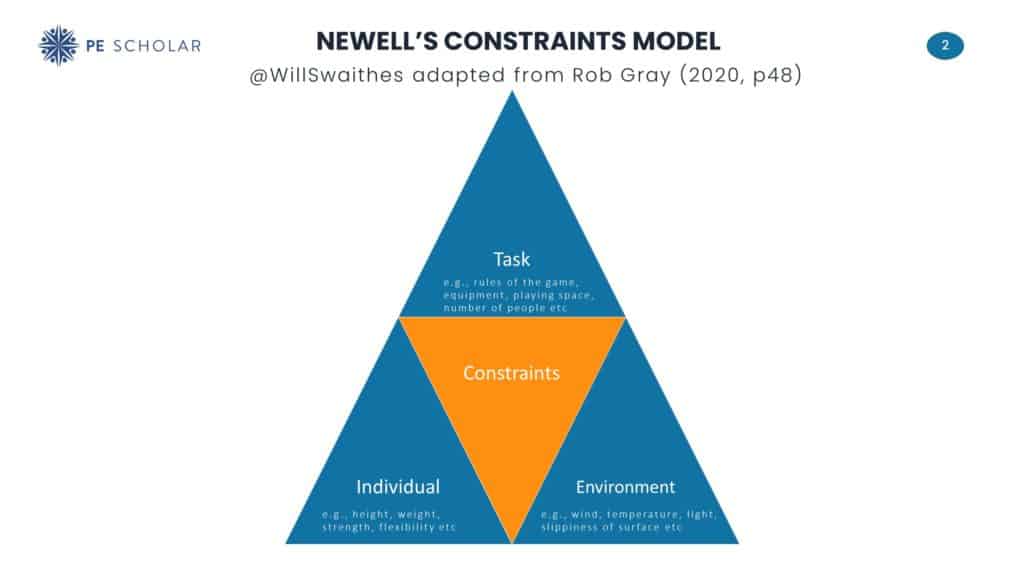

Chapters 4-6: Constraints, perceptions, affordances and the law of attraction

Chapters four to six will take you on a voyage of discovery to further convince you of the science and sense behind investigating more creative, open and ‘game-based’ ways to learn and develop skill. Newell’s 1986 constraints model of coordination is built around a triangle of factors that affect our movement:

When learning a new skill, it is suggested that placing constraints on the task will reduce Bernstein’s degrees of freedom and consequently increase the opportunities for success without removing the authentic situation. Examples shared on pages 47-56 include:

- More talented performers like Nadal have more options available to them in any given situation than you or I thanks to increased speed, strength, flexibility, agility, co-ordination etc and hence have less individual constraints applied in an open environment

- Variations in rain, wind, light and surface properties of the environment will place constraints on all of us, but these can be manipulated in training to aid development

- Task constraints such as ‘the rules of the game, the equipment being used, and the number and spacing of players on a field’ (p49) can most easily be manipulated by the coach or teacher to develop skill:

- Reducing a basketball rim to 8 feet for children

- Using rackets with a shorter shaft or lower compression balls in tennis or squash

- Varying the pitch from a ball machine in practice rather than repeating the same speed and spin

‘Instead of movement techniques being drilled into an athlete through repetition, in this new view of learning, skill emerges in the face of the constraints involved’ (p59). It is suggested that our role as teachers and coaches should be one of developing problem solvers and adaptive players and not focused on providing the one “correct” (technique) solution.

Chapter five explores the idea of embodiment and how our perception of the world around us can vary. For example, fatigued cyclist will perceive the gradient of an approaching hill as steeper than that of fitter or fresher cyclists (p62) and many professional sportspeople have described a sense of the ball slowing down or even getting bigger when they are performing at their best. It goes on to explore the idea of affordances and how we see the world (and situations) based on what affordances (or opportunities for action) are available to us and not always ‘it’s “true” physical properties’ or reality (p67).

Chapter six then gets into the real meat of how we learn to be skilful. It discusses how (and why) it is so hard to get out of bad habits (attractor valleys) and how effective coaching can provide constraints to ensure we train hard to race easy! It goes on to unpick Anders’ Ericsson’s “10,000 hours of deliberate practice rule” (p88) and the learning curve as ‘nice’ but ‘misleading’ fallacies. Gray argues that the key to great coaching is about designing ‘practice environments that foster exploration and promote self-organisation rather than prescribing a solution to an athlete’ (p91).

Chapter 7: Constraints-led Approach (CLA)

Research has demonstrated that copying a “perfect” model is not a very sticky way to learn and consequently when the pressure is on, for example in big match situations, explicit instructions from the coach are rarely reproduced in practice so Gray argues there must be ‘be a better way’ (p98). One potential better way promotes exploration through manipulation of a number of different constraints explored on pages 99-102 to:

- De-stabalise the existing movement (i.e. correct a misconception by focusing on a slightly different task/ movement objective)

- Explore and self-organise (i.e. give time and space to performers to seek out a solution for themselves)

- Amplify information and invite affordances (i.e. increase sensitivity to body position and movement through ‘internal senses of proprioception and kinesthesis’ – for example blocking vision)

- Provide transition feedback about whether search for a better solution is ‘heading in the right direction’ (i.e. rather than just knowledge of performance or knowledge of results)

Small sided games are a commonly adopted and clearly successful example of CLA in action but there is much more to it than that. This chapter also explores the value of analogies like “hit the ball like the shape of a rainbow” rather than “move the racket from low to high” in terms of impact on learners (p107).

Take-aways

I could go on and on, digging into the remainder of the chapters in detail but I don’t want to deny you of the chance to hear these nuggets like the difference between skills and habits (p185) for the first time from the man himself. Chapter 14 for example provides a very convincing case for why this new approach to skill acquisition should also drastically reduce the number of injuries (including repetitive strain injuries and stress fractures). By means of a summary, here are a few highlights I think you should remember, consider and perhaps seek to find out more about:

- We must move beyond the idea of there being one “correct” repeatable technique

- Same, same but different – expert performers achieve the same outcome via a surprisingly wide range of variation in terms of individual joint movements that make up the overall end result

- We must promote creativity and exploration of the joy of movement

- Isolated, decoupled practices are killing youth sport: Task deconstruction via skill-drill style teaching should not be our default starting point – instead seek to simplify and stimulate interest via live situations and play

- Scaling equipment (smaller bats or rackets and bouncier balls or lower targets e.g, basketball rings) holds the key to hooking children in

- Small sided games are just the start of exploring a constraints-led approach (CLA)

- Embrace and encourage the unorthodox and creative solutions

- Use analogies and carefully consider the use of an external focus of attention when coaching or teaching

- Consider giving more time for basic skills to emerge (and programme longer units of work)

- Versatile and adaptive movers will become the best expert performers

Here is a list of other book reviews you might want to check out:

Reviews by topic

Health and wellbeing

Happiness Factories: A success-driven approach to holistic Physical Education (podcast)

Time to RISE Up: Supporting Students’ Mental Health in Schools

Physical Education Pedagogies for Health

Inclusion and social justice

Inclusive PE for SEND Children and podcast

Teaching Disabled Children in Physical Education

Pedagogies of Social Justice in Physical Education and Youth Sport

Pedagogy

Applying Models-based Practice in Physical Education

Perspectives on Game-Based Coaching

The Future of Teaching and the Myths That Hold it Back

Meaningful PE – an approach for teaching and learning

Threshold Concepts in Physical Education

The Spectrum of Teaching Styles in Physical Education and podcast

Reading lists

Also, don’t forget to take a look at these books published by Scholarly – indispensable additions to every PE teacher’s bookshelf.

Responses