This blog series seeks to explore how Physical Education is designed and practised in countries around the world. The intention is to give insight and hopefully inspiration to help improve it for all young people, both now and for the future. This first blog in this series explores physical education in England.

If you have insight from a country we have not yet covered, then we would love to hear from you, please get in touch.

UNESCO published its ‘Quality Physical Education’ (QPE) guidelines for policymakers back in 2017. It includes a great video clip and infographic identifying some of the wide range of benefits of QPE and the following extract reminding us that PE is not just a nice to have in education, it is a human right for all children and young people!

“Every human being has a fundamental right of access to physical education and sport, which are essential for the full development of his personality. The freedom to develop physical, intellectual and moral powers through physical education and sport must be guaranteed both within the educational system and in other aspects of social life.”

The UNESCO Charter of Physical Education and Sport (1978)

Exploring Physical Education in England

In Context

As I am sure all readers are well aware, England is part of the United Kingdom, shares its borders with Wales and Scotland and is in Europe. The population of England has grown from some 53 million in 2011 to a little over 56 million in 2020. The population is spread over 130,000 km2, although capital city London and major cities such as Manchester and Birmingham are densely populated whilst more rural areas like Devon, Cornwall, Norfolk and The Lake District can be far more remote. Consequently, the school system can vary considerably from region to region to help cater for its unique context and that level of autonomy is encouraged by the current government.

There are over 24,000 schools in England, catering for all children 3-18. The majority attend state-funded education in one of nearly 17,000 primary schools up until aged 10 (end of key stage 2) before transitioning to one of c3,500 secondary schools where they sit GCSEs at age 16 and either stay on into the sixth form or transfer to a dedicated post-16 provider for A-levels and other level 3 qualifications. In addition to this, there are a little over 2,300 independent schools which are privately funded, about 1,000 special schools catering for young people with special educational needs and/ or disabilities (SEND) and around 250 pupil referral units (PRUs) which offer alternative provision for young people struggling in mainstream education. These are typically for behavioural or anxiety related issues.

In Policy

The Department for Education (DfE) sets the national curriculum, which is a framework capturing a minimum expectation for study within schools. The extent of central government prescription versus autonomy given to local leaders and head teachers has varied over time, with major amendments made to the national curriculum in 1988, 1994, 1997, 2008 and 2014. The current ‘academy’ structure encourages interpretation of an ambitious yet loose three-page national curriculum for physical education. The subject content and depth of learning differs slightly across the key stages but is underpinned by the following purpose statement and four aims.

Purpose of study:

A high-quality physical education curriculum inspires all pupils to succeed and excel in competitive sport and other physically-demanding activities. It should provide opportunities for pupils to become physically confident in a way which supports their health and fitness. Opportunities to compete in sport and other activities build character and help to embed values such as fairness and respect. Aims:

The national curriculum for Physical Education in England aims to ensure that all pupils:

- develop competence to excel in a broad range of physical activities

- are physically active for sustained periods of time

- engage in competitive sports and activities

- lead healthy, active lives.

The recent 2016 assessment and examination reforms are far more prescriptive and whilst examination PE is an option at key stage 4 (that is currently only taken by less than 20% of students) alongside statutory ‘core PE’ for all, it could be argued that outcomes don’t align perfectly with those we seek for all young people and often places an imbalanced demand on PE staff.

The Department for Education and regulatory body Ofqual have laid out clear expectations on content coverage and a practical activity list of sports that can be used for the 30% of GCSE PE final grades that are made up from practical performance. There are quite a number of sports and physical activities that provide significant educative value within the school system but do not feature on the activity list of what ‘counts’ towards GCSE grades (for example rounders, surfing and fitness).

In Practice

The landscape for Physical Education in England is quite fragmented, there is some incredible practice going on and some joined up collaborative thinking that serves its students very well but unfortunately there is also some poor practice and I think it is fair to say that PE is a bit of a marmite subject whereby some students love it and others hate it. It is clear that this is not good enough! Efforts are being made by the association for Physical Education, the Youth Sport Trust, Sport England and many other partners/ groups of schools and individuals to raise the game at a local level.

Most primary schools catering for students up to the age of eleven are working hard to provide 2 hours of high-quality Physical Education per week and additional physical activity each day to meet CMO guidelines of 60 active minutes. They are supported to do this through ring-fenced Primary PE and Sport Premium central government funding which typically provides an additional £16,000 per year to each school to enrich their offer. Some schools spend this incredibly wisely and provide a rich array of activities both within and beyond the curriculum whilst others could be criticised for not investing wisely in the needs of all children. Accountability of how this funding is spent causes rich debate but on balance it is regarded as a good thing despite some coaching firms and outside providers trying to muscle in on available finances rather than supporting in school staff to upskill and broaden their offer. All primary school aged children are also expected to access swimming to enable all students to swim 25 metres and be water safe. Another challenge and area of rich debate at primary is the lack of time devoted to PE as part of pre-service training for generalists and access to relevant professional development/ mentoring support once in post. An alternative training route as ‘PE specialists’ exists to better prepare individuals for a PE lead role in schools but this approach is not mandated and consequently there is a wide variety in competence and confidence to teach high-quality PE amongst primary school teachers. Despite these efforts to raise the profile and provision of PE and sport at primary, it still remains a relatively poor relation to literacy and numeracy that dominate the focus of teaching and learning in most schools. PE typically happens in the afternoon alongside other art and foundation subjects.

Some secondary schools have a strong culture and tradition of using PE and sport to raise aspirations and support the development of their 11-16 year olds. This is prevalent in the private school system and also as a legacy to a previous Labour government initiative of ‘Specialist Sports Colleges’. The vast majority of secondary schools provided 2 hours of PE per week in 2012 with additional school sport and enrichment opportunities on top of this. Unfortunately, pressure to raise standards with GCSE exam results (especially in English and maths which count as double in Progress-8 measures) has resulted in an erosion of the broad and balanced curriculum that we were once very proud of. Research suggests many schools have reduced the time allocation for PE to one hour at key stage 4 and a worrying number of students are withdrawn from PE for extra English and maths intervention. However, where senior leadership teams are able to see and believe in the power of sport to change lives, there continues to be investment in PE departments and their offer to cater for those with sporting potential and wider participation for all. Changes to Ofsted’s 2019 ‘Education Inspection Framework’ which judges schools and aims to be a ‘force for school improvement’ have refreshed the importance of a rich and varied curriculum as the ‘real substance of education’ with a sharp focus on intent, implementation and impact. As a consequence, many PE departments are reconsidering how to ensure their offer is fit for purpose for all students in preparing them for healthy active lives and not just the needs of the talented few.

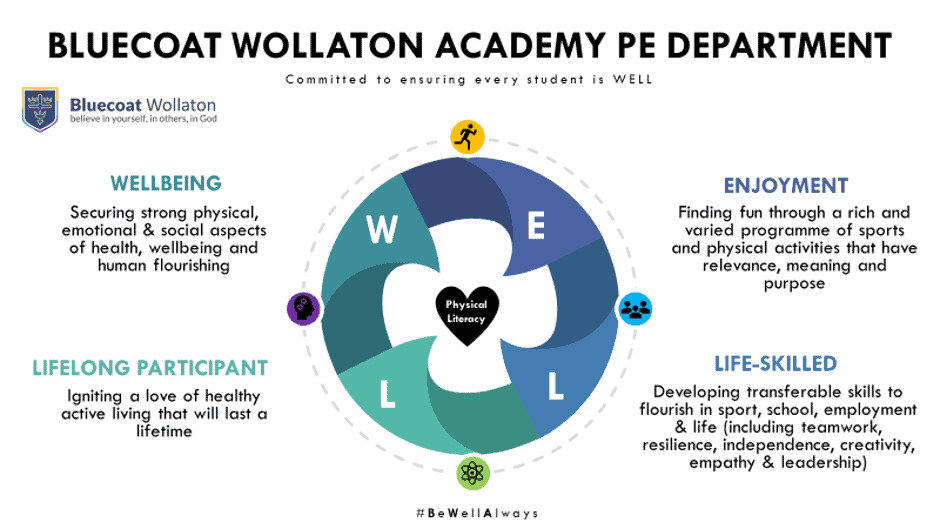

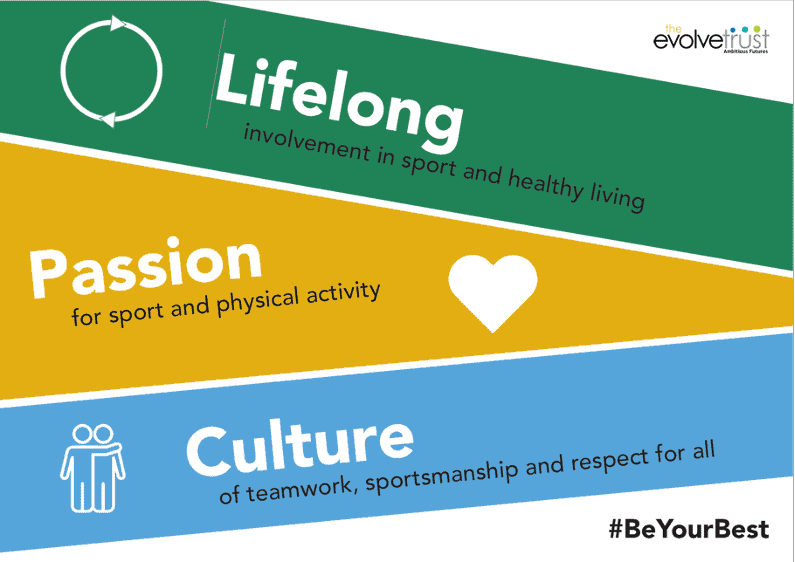

Two examples of schools who have been working on redefining their curriculum intent to help students, parents and other stakeholders to recognise the value of the subject for all children are as follows:

In Conclusion

In England there is an opportunity for creative and carefully considered local leadership in response to specific contexts and, particularly for secondary schools, the establishment of ‘Multi Academy Trusts’ has led to a mixed landscape in terms of the value and expectation placed on physical education.

In recent years there has been an increasing focus on igniting a passion for healthy active living beyond school but the dominant reality is a significant amount of direct instruction aimed at improving physical competence and technique in a variety of traditional sports and activities.

There is a disconnect between ambitions of core physical education for all young people and the measurable outcomes of examination PE (GCSE PE, A Level PE and a number of other vocational sport courses such as BTEC and Cambridge National) that seem to have more of a sport science focus.

It is unlikely England will see an overhaul of the national curriculum in the near future but league tables and Ofsted bear significant influence on the state school system. Consequently, Physical Education in England has suffered some marginalisation but recent concern over student (and staff wellbeing) as well as re-prioritising of a broad and balanced curriculum means that it remains important in most contexts. The primary PE and Sport Premium continues to provide ringfenced resource whilst teacher recruitment and retention within PE is very strong, with many practitioners also holding wider roles such as Head of Year or senior leadership responsibilities.

Takeaways

- The relatively decentralised system enables headteachers (and increasingly executive heads of multi-academy trusts) to meet the minimum expectations laid out in the statutory 2014 national curriculum in a creative and personalised way for their context

- However, the vast majority of schools cling on to traditional subject area and 5 lesson a day, 5 day a week structures of delivery that are focused towards end of key stage 4 examinations

- Ofsted as a school inspection service has a large role to play in what is considered and prioritised in terms of educational provision

- The PE profession is recognised by its ability to innovate, organise and collaborate to better meet the needs of more students and is increasingly aware of the need to focus on affective, social and cognitive domains of learning rather than historic domination of the physical domain

- Some schools still have a way to go to distinguish between physical education, school sport and physical activity and sharpening their offer to ensure the needs of all children are met

If you have a different perspective to that described above or would like to contribute to a similar blog on a different country then we would love to hear from you.

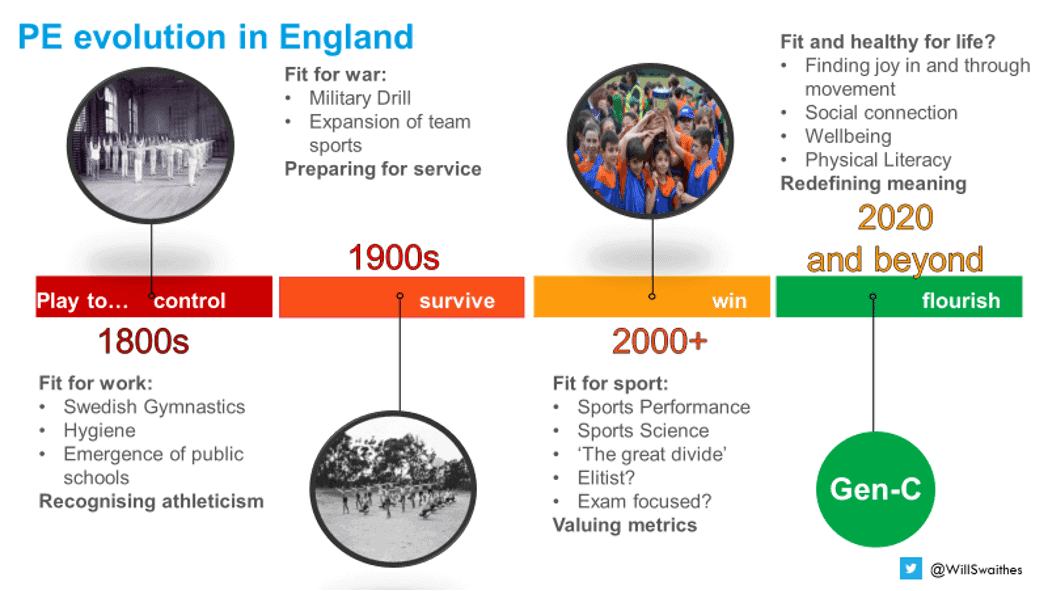

I think it is interesting to see how through time, cultural difference have played a big part in the changing of our policies and curriculum.

Although traditionally ‘clinging’ to the 5 periods per day in lots of schools is still recognised, having alternative curriculum suitable to the type of students and environment is now more relevant and backed by research.

I do agree that there is a disconnect between the PE offer that we provide students that go on to studying Sport & PE at KS4 compared to those that don’t.

The government guidelines for physical activity doesn’t change, so why should the offer to student change?

One thing I would say is many schools now have 1 hour PE for year 10/11 due to exam pressures. However you could argue that if we have done our job in years 7-9 then those pupils are all physically active outside of school on top of that 1 hour a week. That’s our challenge!

[…] England […]

I would agree with Greg above for KS4. Exam pressure plays a huge part in limiting our delivery in school hence why it is imperative we EDUCATE students correctly during earlier KS so that they are able to be better self managers when life pressures exist. Students should be equipped with the skills and knowledge to make positive choices in terms of promotion of wellbeing during such times.

I believe that the disconnect from KS3-KS4 PE plays a bigger part in determining outcomes for students in schools. The imbalanced demand placed on PE teachers limits their capacity to prioritise delivery of a broad and balanced curriculum that caters for the needs of all students.

As a school we also experienced the drop from 2 hours to 1 hour at KS4 due to exam outcome pressures. As a result, it hugely impacted our students motivation levels towards KS4 Core PE and its meaningfulness and we are still suffering from this. However, now this has been increased to 2 hours per week again we are now keen to implement a broader curriculum that is personality driven and provides more student choice.

[…] England […]